This essay was originally published in the book titled DISCURSIVE GEOMETRY AND MORE, published in Poland by Goldenmark Publications, 2023 (in both Polish and English). This collection of essays and monographs was edited by Mark Starel. A PDF version can be viewed at:

Geometric Abstraction and Visual Metaphor (A Thought Experiment)

I have long been intrigued by abstract art’s capacity to deploy visual metaphor in a nonlinguistic mode. For this writing, I am focusing on a specific sub-category of abstract art commonly referred to as geometric abstraction. [1] I am proposing that subtle metaphoric operations often take place in both the creation and the reception of geometric abstract artworks—at least in some instances. Here I am describing metaphoric operations as the transfer of qualities and relations from relatively concrete domains of experience for the purpose of conceptualizing more abstract domains. We now understand (thanks in part to the extensive writings of Mark Johnson and George Lakoff) that metaphor is a critical cognitive mechanism by which we conceptually grasp and explain so much of our inner and outer reality that would be otherwise unfathomable. For example, try describing almost any sort of temporal experience without resorting to spatial metaphors. I am suggesting here that the appeal of many geometric abstract artworks is sometimes motivated by more than their decorative and/or formal qualities—that other levels of meaning-making are consciously or subconsciously prompted via metaphorical mappings.

At the outset I want to state my indebtedness to a wide range of thinkers and researchers operating in multiple disciplines (neural sciences, cognitive sciences, developmental psychology, phenomenology, linguistics, and more) and have, in my opinion, convincingly made the case for a thoroughly embodied cognition [2]. At stake here is a radical refutation of a deep-seated metaphysic and mind/body dualism underpinning centuries of philosophical and religious assumptions of human meaning-making. Here, I am repurposing these insights to proffer an enhanced understanding of this specific art practice. To be clear, I am not attempting to lay down a drawn-out argument but rather to offer, as a thought experiment, an alternative view of geometric abstraction’s potential impact on both artists and viewers.

It is hardly a radical stance to champion art as an alternative mode of representing experience whose mode of meaning-making serves as an antidote to linguistic, propositional, and predominantly linear discourse. However, such laudatory sentiments so often fizzle when confronted with the thorny issue of attributing “meaning” to art practices where nothing is being “illustrated” and nothing explicitly stated. I think we can get past that. For starters, It should be emphasized that any meaning one may assign to an artwork is not some free-floating, transcendent entity that somehow inheres in the artwork; but rather we are talking about a meaningful experience resulting from the interaction between an artwork and a human viewer. Ultimately any experience on the part of that viewer is an amalgam of cognitive and affective operations.

One thing that has been abundantly evident in over several decades of research in the neural and cognitive sciences is that much of human cognition and feeling takes place below the threshold of consciousness. With this in mind, it makes sense that a viewer’s “gut feeling” or their inarticulable fascination with such and such artwork might be generated in part by subconscious responses. Shaun Gallagher (2005) refers to these as “prenoetic” operations that help structure consciousness without it being aware. Consequently, I believe that, with some artworks, these “subpersonal” cognitive operations are likely prompting a cascade of associations and visceral responses of which the viewer may or may not be fully aware. Certainly with most geometric abstract artworks, nothing is illustrated and nothing is explained, yet one’s experienced interaction may very well qualify as “meaningful.”

Now to the essential question: how might visual metaphor be implicated in geometric abstraction? Let’s examine just one among many areas of possibility.

What can be more basic and fundamental to human experience than our ongoing bodily engagement with and within space? Fundamentally, we are biological organisms evolutionarily built for movement in space. All quantitative spatial experience (e.g., degrees of proximity and distance) and qualitative (e.g., relative sense of accessibility, orientation or disorientation) are generated by the kinds of perceptions and the sensory-motor systems at our disposal that operate in concert with not just our very bodily brain but with our entire body. [3] Not only are our movements and interactions with our environment fundamental to our existence, but our innate and learned spatial competencies underpin a great deal of our cognitive grasp of highly abstract, non spatial realms of experience. The philosopher, Maxine Sheets-Johnstone, refers to this as a “bodily logos, a natural kinetic intelligence.” (2009)

And this leads me to geometry, that branch of mathematics indexed to spatial visualization and intuition. Indeed, the Greek root of geo-metry is translated in English as “earth-measurement.” Crucially, geometry—at least its Euclidean version—assumes a naturally continuous space and, within it, the possibility of the movement of objects, forces, and bodies. Geometry entails high levels of symbolization and abstraction to conceptualize what our animate bodies know tacitly.

So how might abstract geometric reasoning play a role in conjuring up foundational, somatic experience in our interactions with artworks? In other words, if I am proposing a body-mind continuum between our primary spatial capacities and their meaningful evocations in artworks, how might these seemingly distinct realms be linked? Not surprisingly my answer is visual metaphor (among other cognitive mechanisms that I’m not addressing). Here it is worth repeating what I mean by metaphoric operations: the transfer of qualities and relations from relatively concrete domains of experience for the purpose of conceptualizing more abstract domains. Here the “concrete domain” is our ongoing bodily interactions in space (“corporal-kinetic patterning.” Sheets-Johnstone, 2009). The “abstract domain” can be almost anything whose explanation and understanding requires or at least will be greatly enhanced by spatial metaphors. I have already mentioned time, but I could add any number of experiences such as, for example, emotional states (e.g. “My mood is a bit low today.” “I’m feeling on top of the mountain.”). Metaphor may not be absolutely necessary, but literal explications of these sorts of feelings would prove at best tortured and likely inadequate to fully convey the sentiment.

With language (written, spoken, or merely thought out) we enlist metaphors with words and sentences. But with static, wordless geometric abstractions we draw from a lexicon of geometric figures that I believe are able to graphically enact inexpressible kinesthetic memories from a lifetime of intimate spatial situations.

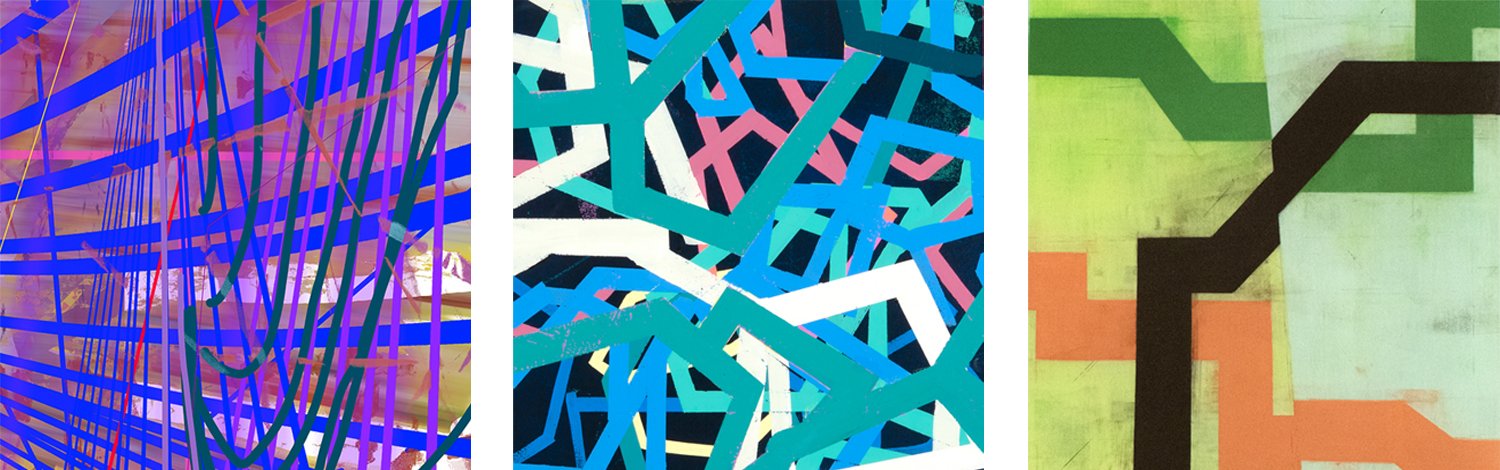

To demonstrate how this might play out with actual artworks, I want to share my own initial interactions with just three artworks [4] that highlight what is arguably the most basic of geometrical primitives—the line. As my focus here is lImited to spatial experience, I feel that lines are apt visual metaphors of movement and directionality. The artworks I am presenting do not invoke overt illusionistic or naturalistic scenes or do their lines function like the more “explanatory” lines of diagrams. Here, lines are in the service of artistic expression and thus should be apprehended and distinguished as much as anything by their qualities (e.g. meandering, straight, hesitant, forceful)—all the better to flex their metaphoric muscles.

Regarding the artworks of Lorraine Tady and Rebecca Rutstein, I need to emphasize that these are my interactions; I make no claim to represent the artists’ intentions or even that they would go along with my ideas about visual metaphor.

Lorraine Tady | Electro Magnetic Projection Wave | 2022 | UV ink on canvas, | 72” x 60” | Courtesy of the artist and Barry Whistler Gallery

At first glance at Lorraine Tady’s Electro Magnetic Projection Wave, I am drawn to the swooping quality of the more salient, curving blue lines that so dramatically traverse the virtual expanse. Of course I am responding to the luscious color and its dynamic composition. However, on a deeper level I am reacting to what I would characterize as a geometric choreography of multiple, interwoven movements. Of course this is a still image and so nothing is literally moving; yet I do not hesitate to characterize it as movement. Why am I doing this? I think it is because of the capacity of lines, as visual metaphors, to facilitate the cognitive transfer of my felt sense of movement to the more abstracted domains of imagination. And this is not a passive imagination, a mere “imaging” (like conjuring up an image of Mickey Mouse). Rather, this is a generative and participatory imagination through which I actively “converse” with the artwork.

Electro Magnetic Projection Wave conjures for me an exceptionally crowded and teeming space, yet ironically a space that mostly (but not everywhere) offers little resistance to unrestrained movement. And it is not just any kind of movement but rapid and intensely frenetic movement. These hyper animated lines neither contain nor connect anything. Rather, they operate as lines of force, many extending far beyond the putative containment of the image format. All this triggers in me both feelings of exhilaration and a foreboding of potential catastrophe. It echoes for me similar kinds of thrills riding roller coasters, only exponentially more intense, as if my coaster’s tracks were entangled among countless others (with no one awake in the control tower!). I also bring to this image (or the image brings to me) still other associations like barreling along expressways at dangerously high speeds.

Rebecca Rutstein | Cosmic Traveler| 2022 | acrylic, flashe, and spray paint on canvas | 36” x 36” | Credit: Courtesy of the Artist and Bridgette Mayer Gallery | ©Rebecca Rutstein

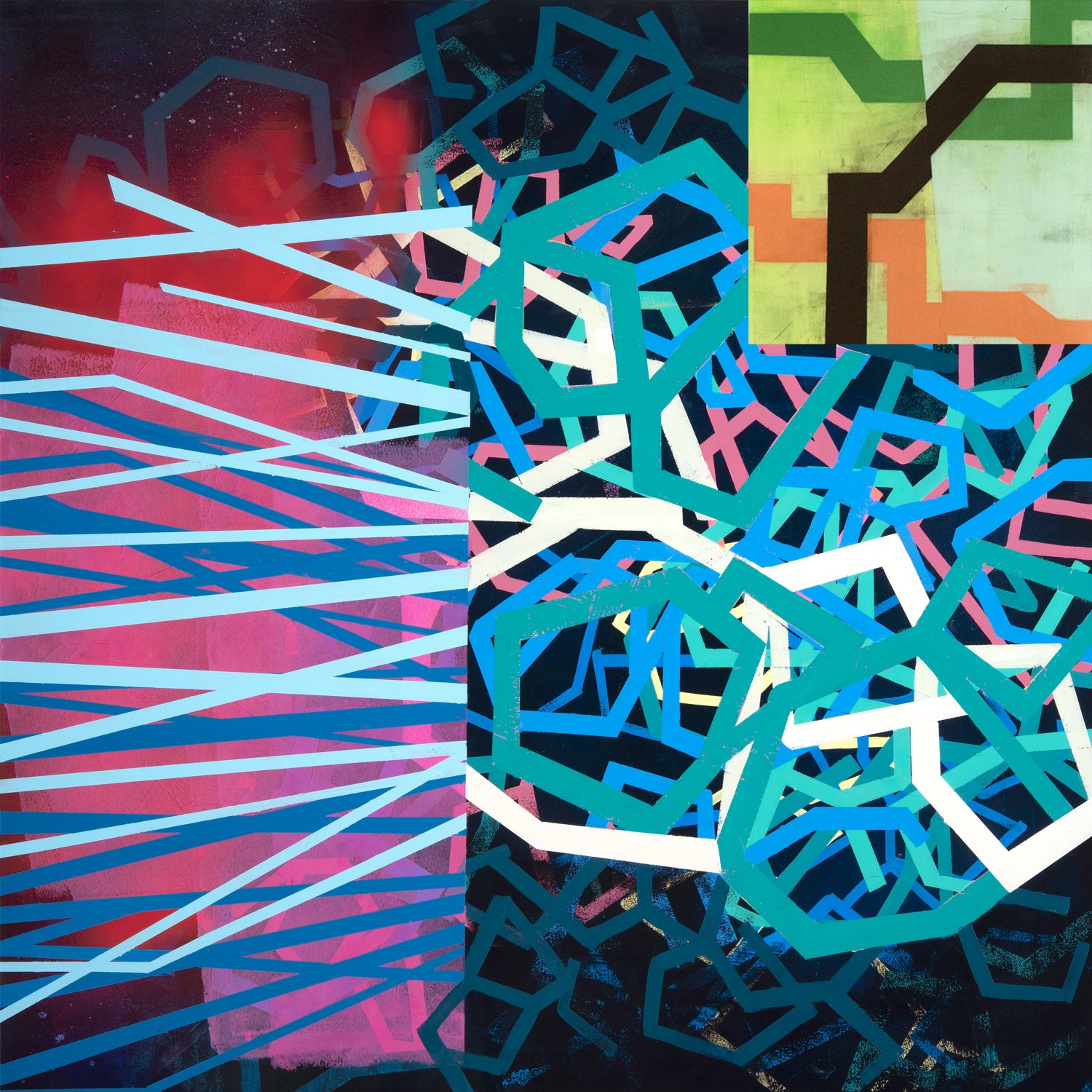

Next up is Rebecca Rutstein’s painting, Cosmic Traveler. Similar to my observations of Tady’s artwork, I am overlooking many important features so as to focus solely on the metaphoric impact of lines. Indeed, there are many similarities, not least of which are their richly saturated colors. Of particular importance for my purposes are the insertions, in both artworks, of those partial edges that constrain if not contain the trajectory of the lines. We see these scattered throughout Tady’s piece and very prominently off-center in Rutstein’s. However, in these two artworks I see significant differences, especially in the qualities and the “behaviors” of the lines. Whereas Tady’s are more elongated and (mostly) curving, Rutstein’s are uniformly rectilinear and angular, thus evoking very different kinesthetic associations. As well, Rutstein’s lines are much wider relative to their actual or projected length, and this, I feel, is significant; the width/length ratios of lines often metaphorically signal different velocities. Although I initially regard Rutstein’s lines as moving, the nature of their motion is radically different than Tady’s—and by extension, the kinds of associations they summon.

Unlike the unrestrained exuberance of Tady’s lines, Rutstein’s velocities are far more attenuated because of the different ways they function. Are the seemingly “faster” blue lines on the left functioning solely as moving lines, or are they connecting lines that link unseen elements beyond the frame? Or that interlaced tangle of lines on the right: are these lines moving, or are they functioning as containing lines, enfolding shifting, honeycombed pockets of space? As metaphoric vehicles of meaning-making, these colliding constellations of lines evoke for me not a single spatial continuum but multiple, interpenetrating spaces—not a plenum affording effortless passage but one of enormous density and structural complexity, one well beyond my capacity to navigate. It is hard to know where to enter or where to go (and if I were to go, would I actually get there?). Like with any artwork, my responses vary according to my state of mind, but generally speaking, I find that these complex geometric structures offer a perfect analog to the perplexing, networked world around me—manifold interlocking “spaces” for which I am woefully unequipped to grasp, much less to navigate.

Steven Baris | Never the Same Space Twice D36 | 2022 | oil on Mylar | 24” x 24”

Finally I will turn my attention to a painting from my Never the Same Space Twice series. This body of work is tethered to my ongoing investigation that I have titled the Expanded Diagram Project. Here I explore the intersections of what I describe as “diagrammatic thinking” and a broad range of historical and contemporary artistic practices. [4] Indeed, diagrammatic thinking is an essential component of this series of paintings. And more to the point in this context, diagrammatic practices and metaphoric operations are not mutually exclusive with not only my work but with a broad range of geometric abstract practices. In many instances, these are two sides of the same coin.

Unlike my third-person observations of the previous artworks, I speak here from a first-person perspective that affords me the license to address influences, intentionalities, and felt meanings. With Never The Same Space Twice D36, I deploy lines to evoke hybrid topological route maps. As with all of the works in this series, the lines map no specific or actual space(s), but rather they enact a virtual experience of navigating indeterminate terrains marked by discontinuities, disruptions, and detours. A common thread connecting nearly all facets of my art is my obsession with the challenges of spatial orientation and way-finding in our rapidly re-engineered, networked ecosystem. For me, topological mapping offers an apt metaphoric schema to represent my deeply felt sense of the fragmentation of contemporary spatial and temporal experience.

The very ground of the this painting is subdivided (and I would add, “fractured”) into four contiguous sections abutting each other at various angles. The broad rectilinear lines—each differentiated by contrasting colors and values—“make their way” haltingly across the painting. The lines’ “movements” are, at various junctures, suspended, redirected, sped-up or slowed-down. Implicit within the broader analogy of a route map, movement and navigation are inextricable. To navigate is to move, or more specifically, to plot or enact a sequence of “next moves” so as to insure successful passage through imminent spaces and temporalities.

And so again I return to lines’ metaphorical capacity to effect a transfer from “source domains” of real-world experiences of movement (or of resistance to movement) to “target domains” of the imagination and the aesthetic. It’s though the deployment of lines that I am able to re-think and re-feel my life’s load of alternately losing and finding my way.

In summary, I hope I have offered an alternative understanding of how seemingly inert, two dimensional geometric figures can body forth a broad range of associations, facilitated in part by visual metaphoric operations. [5] Ruminating as I have on these artworks, I relied almost entirely on metaphorical language; literal statements were few and far between. By using written words to deploy those metaphors, I tried to evince feelings felt and perceptions perceived, all of which were derived from my nonverbal interactions with silent, geometric visual displays—that is, from geometric abstract artworks.

Notes:

1. Art categories are notoriously slippery, geometric abstraction being no exception; I try to avoid over-reliance on them. However, for the present discussion I am offering a working definition that I hope is adequate to account for the countless variations of self-described “geometric abstract” artworks produced since the early 20th century. Here we go: an artwork eschewing naturalistic forms and space that employs geometric primitives (lines, triangles, squares, etc.) as its primary compositional elements.

2. Here is a partial “tip of the iceberg” list of influential writers: Mark Johnson (1987, 2007), George Lakoff and Mark Johnson (1980,1999), Maxine Sheets-Johnstone (1999, 2009), Francisco J. Varela, Evan Thompson, and Eleanor Rosch (1993), Antonio Damasio (1999, 2012), and Shaun Gallagher (2005).

3. It is worth noting here the discoveries in the neural sciences have revealed neural activity in the premotor and motor areas of the cortex that are activated not only when a subject executes a movement in space but also when a similar movement is merely observed, AND when it is imagined! So it is not hard to conceive that art and cultural representations more generally would evoke or elicit our conscious or unconscious response to remembered and/or imagined spatial “situations.”

4. Different parts of the Expanded Diagram project can be viewed at https://www.stevenbaris.com/about-the-project, stevenbaris.com/about-diagrams, stevenbaris.com/diagrams-and-art, and stevenbaris.com/blog . I should add that both Lorraine Tady and Rebecca Rutstein were subjects of my Expanded Diagram blog.

5. I need to point out that the metaphoric reach of geometric abstraction is hardly limited to spatial experiences, and of course lines are only one of many geometric forms and figures at its disposal.